NEED TO KNOW

To get better acquainted before they set out on their real-life road trip, Steve Martin paid a visit to the Candy home in Mandeville Canyon. “I had thought he was fantastic on [Second City Television], of course,” says Martin, “so I already had great respect for him and thought he was really funny. It was a little awkward at first because you’re getting to know someone, but eventually we just really made each other laugh. Well, at first, we weren’t trying to make each other laugh. We were just being nice and saying hello.”

During the 85-day shoot, Martin and Candy would be spending most of their time together, much of it on location in many of the northeastern U.S. locations depicted in the film. Hughes’s race to make the Thanksgiving deadline became as chaotic as the tale he was shooting.

“Everything that happened onscreen also happened in the production of the movie,” says Martin, “missing planes, not having the right weather, landing somewhere in Rochester then realizing no, the snow is in Buffalo now, so we had to move the entire production to follow the weather patterns.”

Filming commenced near Buffalo, N.Y., on March 2, 1987, on an unopened stretch of Route 219. To alleviate some of the stress during shooting delays, long days and cold weather, Martin and Candy developed a running comedic banter between them on the set.

House of Anansi Press

“John could always make me laugh,” says Martin. “He had this bit he would do where he would pretend that he was in one of those old Italian gladiator movies that had been dubbed badly into English. He’d say something like, ‘Kneel before your queen, Centurion,’ but he would move his mouth after he’d finished the line. It just made me laugh every time. It’s hard to explain this, but it was something to do when the shoot was getting long and difficult, because we were actually in those freezing circumstances. We had this thing, we’d come in in the morning and we’d fake frustration by faking a punch-out to each other. I’d pretend-hit him in the face and then he’d pretend-hit me back, and we would both just laugh and laugh at that. And it’s hard to explain why that was funny. It was just, everything was so difficult that you were just taking it out on each other.”

Martin and Candy were both as excited about working with each other as they were about the ways in which the Hughes script would allow them to stretch as actors. For Candy, getting to play the unsophisticated traveling salesman, a big man like himself, gave him an opportunity to showcase both his flair for broad comedy and, for the first time onscreen, his innate vulnerability. Likewise, the relative straightness of Neal Page allowed Martin, the erstwhile “Wild and Crazy Guy,” to stretch his dramatic muscles.

“It wasn’t ‘sketch comedy,’ where John had started,” says Martin, “and it wasn’t standup, as I had done. Something you face on every movie, is ‘How big do you get?’ or ‘How small do you stay?’ Planes, Trains walked that line between the characters feeling very real, but then there are these jokes where you get punched in the face and almost get run over by a car or washing my face with John’s underwear.”

Hughes’s sprawling 150-page script was considered long for a broad comedy with commercial aspirations. “A typical script is around 110, 120 pages,” says Martin. “So I asked Hughes, ‘What are you going to cut?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Cut?’ Meaning nothing.”

Besides a hefty word count on the page, Hughes was equally fond of letting certain of his actors ad lib if he trusted their improvisation skills. Candy and Martin, two of the sharpest comic minds of their generation, quickly found a natural groove together.

Martin remembers plenty of this riffing during a scene in which actor Michael McKean played a state trooper. “It’s, like, 10 degrees outside on this stretch of road,” says Martin, “and while we were cross-talking this dialogue, I would ad lib something, then the crew would have to turn the camera around to shoot the other side to get my coverage. Then John would ad lib something, so Hughes would say, ‘Well, we got to get that on film.’ So they turned the camera back around, which is a big deal. Turning the camera around is what takes all the time.”

Paramount Pictures

McKean recalls that after a full day of improvising against a background of sunny skies and green grass, the three actors went to dinner immensely satisfied with what they had come up with. But when they returned to their location the next morning to shoot the reverse angle “pickups,” they discovered that intense overnight snow squalls had blanketed their little stretch of Route 219 under a coat of white, forcing Hughes to shoot the entire sequence again, from the beginning.

For McKean, there was at least one upside — more time to get to know Candy. “I became quite fond of him,” says McKean. “I was already a big fan of SCTV, and while that whole cast was just phenomenal, I always thought there was this kind of sweetness about John.”

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

As the shoot dragged on, both Candy and Martin realized that, while Hughes the screenwriter had written brilliant dialogue, Hughes the director was more than willing to burn through multiple takes of the same scene, allowing endless improvisation in pursuit of capturing “lightning in a bottle.”

“We both had a good insight into our comic timing,” says Martin, “and we liked the scenes [as written]. These characters were so well defined that swapping lines would not be logical, but we came up with stuff on the set and Hughes was all for it.”

Paramount Pictures

And so was Candy, at least at first. “We’d still be in character,” Candy later recalled, “and we wouldn’t hear ‘cut!’ Our eyes kind of flashed just a little. You realize he’s not going to cut … so then you stay in character, and you go, ‘Well, what about this?’”

Fearing that the best parts of the script might be lost amid the hours of freestyle riffing, Candy and Martin made a kind of pact to rein things in. “We said, ‘No more ad libbing,’” says Martin, “‘because this is going to go on forever,’ and we mostly obeyed that rule. John and I really liked each other, so we never thought about chemistry, we just did what we were supposed to do and there was never any hint of competition. I think it’s like the old cliché about the tennis match, that you play better if you’re playing against someone really good.”

The PEOPLE Puzzler crossword is here! How quickly can you solve it? Play now!

Among the most talked-about sequences in Planes, Trains and Automobiles, when the reluctant travelling companions are forced to share a tiny, single bed in a rundown motel, was born out of improvisation.

“John ad libbed that line when I say, ‘Those aren’t pillows,’ which was made up on the set,” says Martin, “and Candy gets up and awkwardly starts talking about ‘manly’ things like sports teams, ‘How about those Bears?’ And it’s just funny.”

Candy thought so too, later recalling that the only hard part of filming the scene was doing it over and over again for Hughes and his punch-drunk crew. “They had the camera rigged up over our heads,” Candy explained. “You’d see the cameras start, you know, they’d look at us and we’d see that, we’d start laughing and then everybody started. ‘Now kiss his ear, nibble it, just nibble it, just — lower, lower.’”

Hughes was also known for pre-selecting his preferred music cues for a given scene, and in this case, he had asked that Emmylou Harris’s cover of Patsy Cline’s “Back in Baby’s Arms” be played back, loudly, on the set while Martin and Candy squirmed on their comically cramped mattress. “Every time we got in that position, we’d hear the music,” Candy later remarked, “and we’d start laughing. Then we’d settle down and we’d see the cameras start shaking … everybody lost it.”

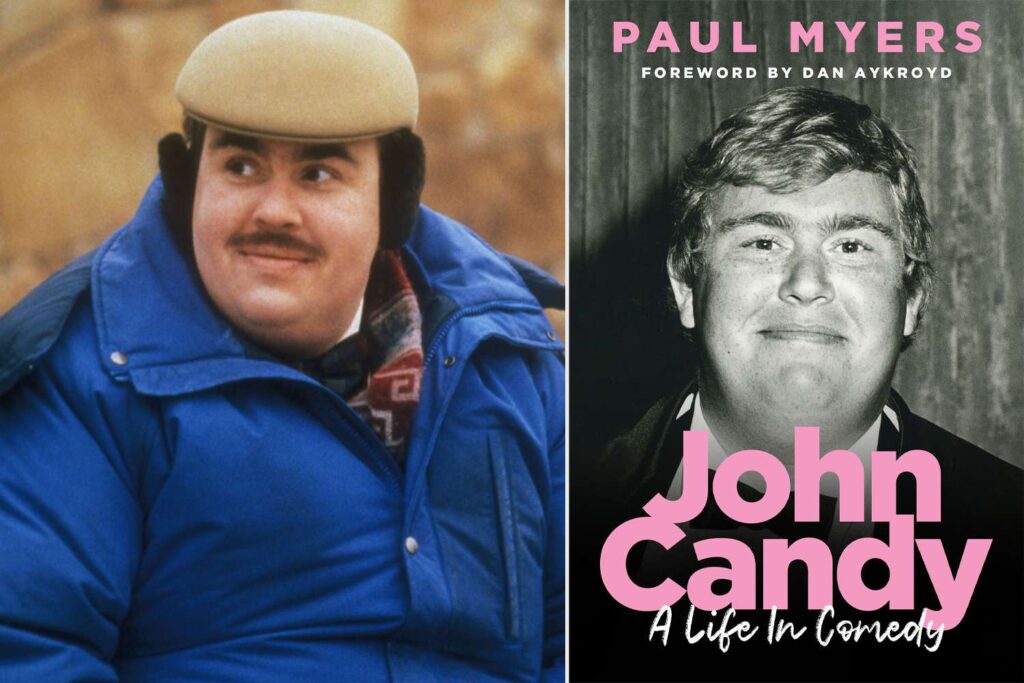

Excerpted from John Candy: A Life in Comedy, by Paul Myers. Reprinted with the permission of House of Anansi Press.

John Candy: A Life in Comedy by Paul Myers is available now, wherever books are sold.