NEED TO KNOW

When an unknown Jeff Buckley stepped onstage for his first New York performance, at a 1991 tribute to his father, folk-rock legend Tim Buckley, Rebecca Moore wasn’t expecting much.

Moore, part of the crew that night, had grown up in the city’s avant-garde scene and wasn’t easily impressed by aspiring artists. Then Buckley opened his mouth: “He seemed to give in to a force,” says Moore, who later became Buckley’s partner, and his muse. “His essence was music. I’d never seen music flow out of somebody like some uncontrolled spirit.”

Buckley’s voice, a haunting, transcendent tenor with a nearly four-octave range, is most familiar from his iconic rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” which has more than 407 million Spotify streams. But for an artist who released just one album in his lifetime, he’s had an outsize influence: Adele, Radiohead, Lana Del Rey and Coldplay’s Chris Martin (who said Buckley’s music was “responsible for us being a band”) all point to him as inspiration.

“Jeff cuts right to your heart,” says director Amy Berg, whose new documentary It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, in theaters starting Aug. 8, unveils the tender, surprisingly funny man behind the brooding artist and explores the singer’s conflicted relationship with his his singer-songwriter father — and his own fame, cut short by his shocking death in 1997 at the age of 30.

Magnolia Pictures

“He had this beautiful gift and triumphed over a lot of personal things to put it out there,” says Moore. “For that, we’re lucky.”

Born in Anaheim, Calif., in 1966, and known by his middle name, Scottie, Buckley was raised by Mary Guibert, who had him when she was still in her teens. She remembers hearing him vocalize to the radio as an infant: “I’d stand in the doorway and weep.”

Courtesy of the Estate of Jeff Buckley

His dad, Tim Buckley, whom Guibert met when they were both in high school, left to pursue music before Jeff was born. At 8, he had his only encounter with his father, by then a folk singer with a large following. He watched him perform once (a “magical moment,” Guibert says) and stayed with him for a few days. “But instead of being present with his newly introduced son, he was doing cocaine all night and sleeping all day,” Guibert says.

Two months later, in June 1975, Tim was dead of an overdose at age 28. Scottie, who until then used his stepdad’s surname, Moorehead, began going by Jeff Buckley. By high school, music was his driving passion.

Though Buckley followed his father’s path (and bore a striking resemblance to him), “that ghost haunted him,” says Berg.

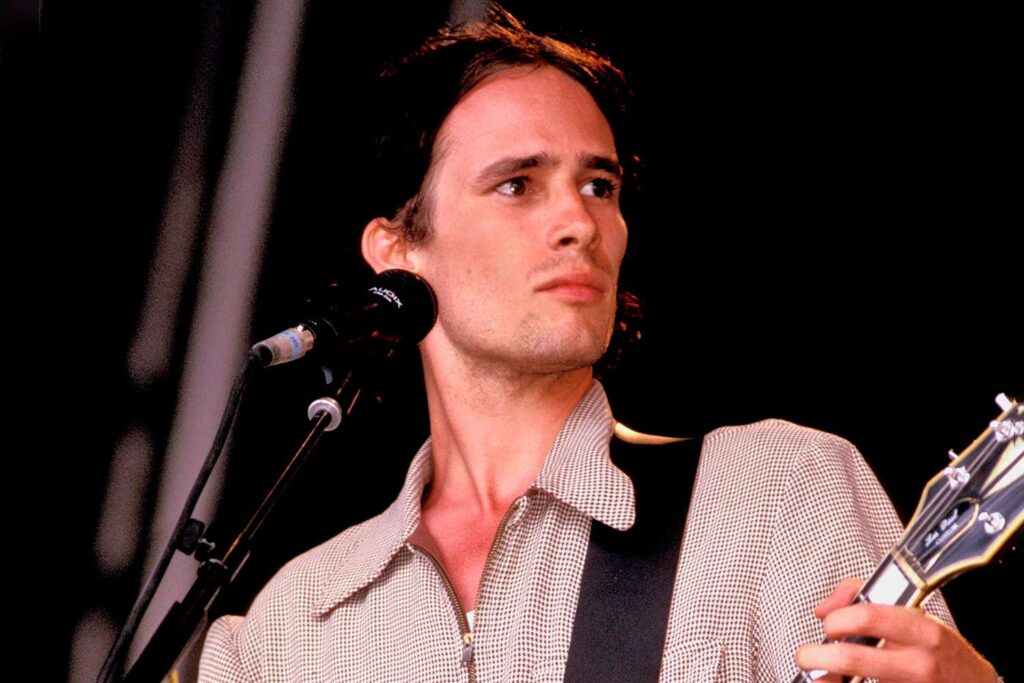

Brian Rasic/Getty; Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Asked about the musical “gift” he inherited from his father, Buckley would shoot back: “The only thing my father ever gave me was a fleeting glimpse.”

He was conflicted about coming to New York in 1991 for his dad’s tribute, but that, along with nights performing covers of Nina Simone, Edith Piaf and Led Zeppelin and his own songs at the East Village coffee shop Sin-e led to a multimillion-dollar deal with Columbia Records. The label was home to giants, like Billie Holiday and Miles Davis, who were inspirations for Buckley. “You had Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and then Jeff Buckley,” says his former tour manager Gene Bowen of the label’s roster. “There was a lot of pressure.”

Buckley delivered his debut, Grace, to critical acclaim. Buckley’s own idols. Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page called it one of his favorite albums of the decade, while David Bowie said it was the album he’d want to take to a desert island.

Columbia Records

But the singer was dismayed that his looks seemed to receive nearly as much attention as his music. “I think it was a challenge for him,” says Berg. ” The label was pushing the marketing of this gorgeous young guy they just signed, and he just wanted to be known as this musician.” Once when presented with his picture in People’s 1995 Most Beautiful issue to sign, the singer “took the Sharpie and scrawled across his face,” his mom recalls.

The demands of fame and touring fractured his relationship with Moore, who’d fallen for Buckley’s open spirit. (Buckley’s playfulness — including his penchant for recording hour-long outgoing messages in the style of old radio plays — is captured in Berg’s documentary, which includes those recordings.)

“He wanted to connect with everyone,” Moore says. Even dogs he’d pass on the street: “The next thing I knew, he’d be rolling on the dirty sidewalk with this dog.”

By 1997, the stress of putting out a second album weighed heavily. “He was struggling,” says Moore, who recalls that Buckley began to wonder if he might be bipolar.

He moved to Memphis to write in solitude and rediscovered his voice. But the day he was to start recording in May 1997, he stopped off at a tributary adjacent to the Mississippi and, singing along as Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” played on a nearby stereo, waded into the water, sober and fully clothed. It was “a moment of joy that was a 100 percent patented Jeff-type move,” Moore says.

A wake from a passing riverboat pulled him under. Authorities found his body six days later, and an autopsy later determined he had one beer and no drugs in his system. His death was ruled accidental.

Neilson Barnard/Getty

“Once in a lifetime, if you’re lucky, an artist comes through who is channeling something,” says Moore. “They’re not just an accomplished person or a great personality or extremely beautiful, or whatever. To come in the presence of an artist who was such a channeler of spirit through their work is such a privilege. He was just a very sweet, alive person.”

And Buckley himself imagined sharing his music for years to come, says his mother.

“He wanted to live to an old age,” Guibert says of her son. “He fantasized about being onstage in a wheelchair. He envisioned a life in which he could put his guitar on his shoulder, and people would want to hear him sing, and he could write whatever was in his soul. And that would be all life would ask of him.”