NEED TO KNOW

Ed Sullivan, the legendary TV host whose eponymous variety show helped launch Elvis Presley and the Beatles to superstardom, was one of the key figures in the early evolution of rock & roll. Before American Bandstand’s Dick Clark and Soul Train’s Don Cornelius later set the standard for youth-oriented music programs, Sullivan was America’s first oldest teenager.

He quietly helped change television, music and American society by going against the social mores of his time and deliberately seeking out Black talent to spotlight on The Ed Sullivan Show. He was, in a sense, the anti-Lawrence Welk.

The new Netflix documentary Sunday Best, which premieres on July 21, charts Sullivan’s life and career, from his childhood in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood to his 23-year run as host of TV’s groundbreaking The Ed Sullivan Show.

The primary focus of the film — as shown in the clip above, which has been exclusively shared with PEOPLE — is exploring the ways in which Sullivan championed Black artists during a time of deeply ingrained racism and segregation. To tell his story, Sunday Best uses Sullivan’s own words from thousands of columns, articles and interviews along with recreations of his voice.

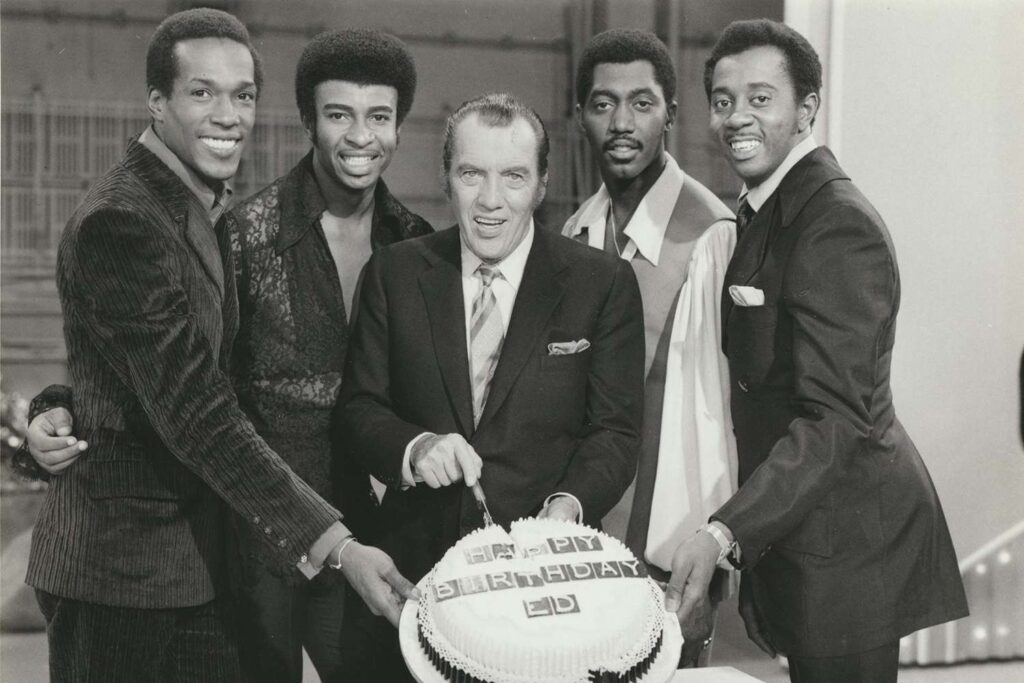

Courtesy of Netflix

As he says early in the documentary, via one of those recreated voiceovers, when The Ed Sullivan Show (initially named Toast of the Town) debuted on June 20, 1948, “There were pressures to keep television lily-white.”

As Motown Records founder Berry Gordy points out in Sunday Best, the Black presence on television at the time was limited, in part, to the buffoon title characters on the sitcom Amos ‘n’ Andy. And there was also Beulah Brown, a domestic worker who was introduced on the radio in the late 1930s voiced by a White man.

By the time Gone with the Wind Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel took over the role of Beulah in 1947, three years before Beulah transitioned from radio to television, Sullivan was on the cusp of launching the variety show that would go on to shake up racial representation on TV. He did so over the objections of network gatekeepers as well as segregationists and the Ku Klux Klan, who are shown in clips throughout Sunday Best to underscore the division and danger of the times.

Sullivan’s professional destiny may have been partly decided after an incident that happened in 1929 when he was working as a journalist and covering a college football game.

“I was then sports editor at the New York Evening Graphic and NYU booked a game against the University of Georgia to be held in New York,” he recalls in Sunday Best. “And I was sickened to read NYU’s agreement to bench a negro player for the entire game. I felt this issue was important enough to be fleshed out publicly.”

“What a shameful state of affairs this is — Myers risking his neck for a school that will turn around and bench him because the University of Georgia asks that the color line be drawn,” he wrote in a column titled “N.Y.U. Draws Color Line.” “If a New York university allows the Mason Dixon Line to be erected in the center of its playing field, then that university should disband its football season for all time.”

Courtesy of Netflix

Sullivan may not have been able to do much to end segregation in college sports at the time, but when he landed his own show on the CBS network in 1948, he made it his mission to change the face of entertainment in an unprecedented way, by showcasing the Black talent that television, for the most part, was ignoring.

Of course, the powers that be erected giant roadblocks to try to hinder him — and failed.

“You’d be amazed at what I couldn’t do,” the Sullivan voiceover says in the documentary. “If I had a Black performer on, CBS censors would warn me not to get too close. I was told not to shake hands with [boxing heavyweight champion] Joe Louis [he did anyway]. I was criticized when I put my arm around Ethel Waters. But in every day and age, and particularly right now, the power of simple words is of tremendous importance in the ideological clash.”

Sunday Best, named for the day of the week The Ed Sullivan Show aired, includes vintage performance clips from some of the Black acts that were featured on the program, which ran from 1948 to 1971, including Billy Preston, Jackie Wilson, Bo Diddley, James Brown, Ike and Tina Turner, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Harry Belafonte, Nat King Cole, Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, Mahalia Jackson, Stevie Wonder, the Supremes and the Jackson 5. A number of Black stars also pay tribute to Sullivan in interviews: Smokey Robinson, Oprah Winfrey, Dionne Warwick, Jackie and Tito Jackson, Gordy and Belafonte.

“Imagine being 10 years old, on welfare, watching The Ed Sullivan Show, in a culture that had no Black people on television,” Winfrey says in Sunday Best. “And when you first see somebody that looked like you, it represented literally possibilities and hope.”

Sunday Best premieres July 21 on Netflix.