NEED TO KNOW

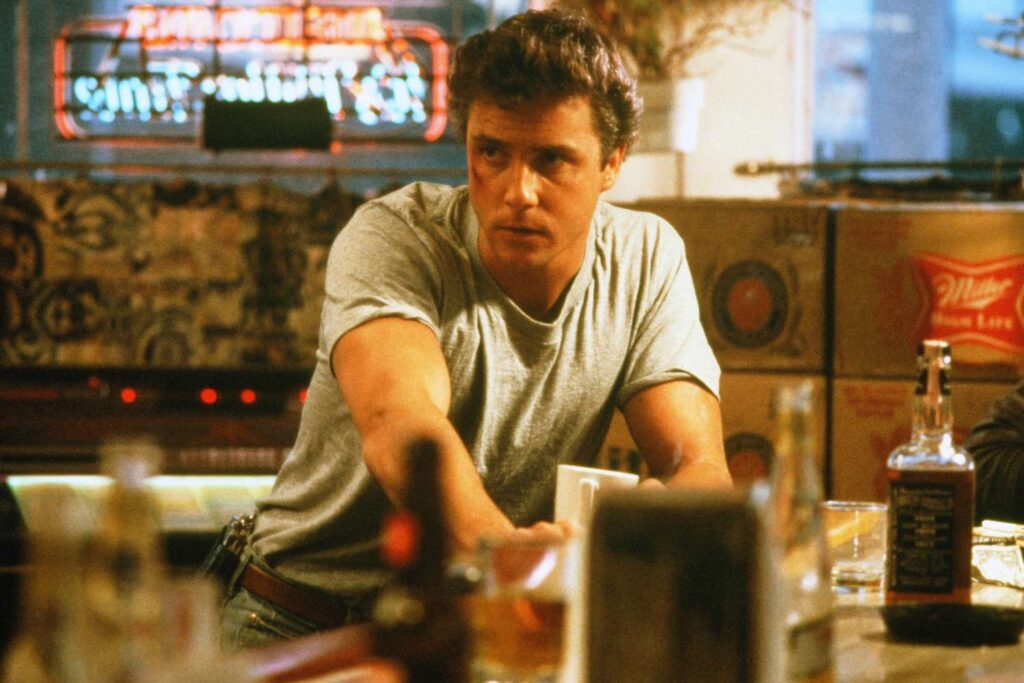

The stylish crime thriller To Live and Die in L.A. may have debuted 40 years ago this month, but star William Petersen’s memories of filming the 1985 neo-noir remain vivid in his mind.

Ahead of a 40th Anniversary screening and appearance at Beyond Fest at the American Cinematheque, Petersen, 72, looks back at the film that provided his Hollywood breakthrough, directed by the legendary filmmaker William Friedkin.

“Standing up on top of the bridge before the jump was pretty big,” Petersen chuckles during an exclusive chat with PEOPLE, recalling the iconic scene atop the Vincent Thomas Bridge in San Pedro, Calif., nearly 400 feet above the Los Angeles Harbor.

“That was an early morning Sunday, like a 7 a.m., chilly Sunday morning, and I’m standing on the railing above this bridge holding onto a bridge cable. And I’m like, ‘What in…? How did I get here? Wait a minute – just a little while ago, I was in Canada doing a play. How did I get on top of this bridge?’” he recalls. “That was a great day of shooting.”

The entire experience of shooting To Live and Die in L.A. — considered one of the all-time best films centered in Los Angeles and one of the ultimate ‘80s-era action thrillers — was a heady one for Petersen, he explains, having been unexpectedly plucked from a rising career as a theater actor for his first starring role in a film. The big break would lead to a long Hollywood career, including headlining Michael Mann’s Manhunter (featuring the first screen appearance of a pre-Silence of the Lambs Hannibal Lecter) and the long-running forensic drama CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.

Moviestore/Shutterstock

Petersen says Friedkin, who’d previously dazzled movie audiences with thrillers including The French Connection and The Exorcist, was looking to populate To Live and Die in L.A with a cast of fresh, unknown faces. “It was all theater guys, because he didn’t want any names,” he explains. “He felt he wanted to recreate what he had done with French Connection, which did not have anybody that anybody knew.”

A rising stage star as a young member of Chicago’s fabled Steppenwolf Theater company, Petersen was appearing in a production of A Streetcar Named Desire in Stratford, Ontario, Canada, when opportunity came knocking, thanks to a tip from one of Steppenwolf’s founders.

“My pal Gary Sinise…went in to interview for it, and I think [the casting director] said to him, ‘Yeah, great, really nice to meet you and everything, but you’re not going to get the part. But do you know anybody in Chicago who could really play this part?’” Petersen reveals. “Because we were all happening in Chicago in the early ‘80s – there was a lot of focus on what we were doing in the theater back then, and Sinise, being a mensch, said, ‘Well, yeah, kind of. I mean, I know this guy, Billy Peterson – he might be perfect for this.’ “

Petersen recalls the casting director arriving at one of his performances, asking to meet him, urging him to make a trip to New York to meet with Friedkin. “I was like, ‘Well, I’m doing this play up here. I can’t go anywhere.’ He says, ‘Well, how about on your day off?’” he recalls. “So I literally flew down there on a Monday between shows, and I had no idea what was going on…I ended up going from LaGuardia to this guy’s apartment, and then he put me in a cab and sent me over to Friedkin’s place on the east side…and then I sat with Billy Friedkin for an hour.”

After some chit-chat with Friedkin and reading a couple of pages of the still-in-progress script, the filmmaker surprised Petersen with a sudden offer. “He said, ‘You want to do my movie?’ ”

MGM/UA Entertainment Co./Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty

“And I was like, ‘What?’ This, this is not how this stuff happened – I didn’t even have an agent or anything, right?” Petersen laughed, noting that he reached out to another actor friend from Steppenwolf for guidance. “I had to call [John] Malkovich because he made The Killing Fields and was down in Texas making another movie. And I said, ‘What’d you get for your movie? They’re asking me how much I want. I have no idea what to do!’ ”

Petersen quickly discovered that Friedkin was also unexpectedly collaborative with the first-time leading man’s immediate, broad input when it came to crafting his character, hardboiled Secret Service agent Richard Chance.

“[Friedkin asked me] ‘What kind of vehicle do you want for your personal vehicle?’ I was like, ‘I think he would have a pickup truck with a roll bar.’ And they just did it all,” he says. “And then the next thing I knew, I was out in L.A. living with the casting director in a house up in Bel-Air, and we were just running and gunning all over L.A. I learned L.A. like the back of my hand just from doing the three months out there with them, because we shot all over the place.”

“Half that script was improvised,” he reveals noting that he and his fellow cast of unknowns — including now-acclaimed character actors Willem Dafoe as the drug kingpin antagonist and John Turturro as a criminal lowlife, future Mad About You costar John Pankow as Petersen’s partner and model-turned-actress Darlanne Fluegel as an informant caught between Petersen and Dafoe – were encouraged to carry scenes out well beyond their scripted dialogue.

“We didn’t stop until he said ‘Cut,’” the actor recalls. “Even if we hadn’t rehearsed the rest of the scene or whatever, we just went on with it. And there’s a few scenes in there where he just kept the camera going and stuff happened. It was a remarkable experience, really…because Billy knew how to do it, man.”

That sense of immediacy came in handy when shooting some of the film’s signature action sequences, especially a memorable moment when Petersen, in hot pursuit of a quarry, hops atop a moving handrail at Los Angeles International Airport and dashes along the top. Airport officials had nixed the stunt.

“They didn’t want us to do that,” Petersen says. “We had gone out there and set it up to do it, and then the head of the airport thing came along and said, ‘No, we don’t want him jumping up on this thing. This is going to cause all kinds of problems for us,’ and whatever. And so Billy would say, ‘Well, okay, I’m telling you now: you’re not allowed to do that!’ And then he’d pull me aside and go, ‘Just do it. We’ll roll on it and just say you just couldn’t help yourself.’ ”

Another key learning experience came when Petersen was allowed to stunt-drive a car during the film’s unforgettable, nail-biting chase scene across a series of L.A. landscapes.

“At one point, they had a camera mounted on the right side of the back, off the back passenger seat,” he remembers. “[Friedkin] was filming it along the side, and I was doing the driving. The camera wasn’t on me, but by trying to get between these two trucks, I ended up knocking the camera off the car. I caught an edge of the truck, and I think the cameras were like 200,000 bucks or something. And Billy was like, ‘Okay, well, that’s an insurance claim.’ And back we went!”

“I mean, we never stopped. We shot and shot as fast as possible,” he adds. “I think that’s how he did it on French Connection, too.”

Alamy

Petersen got one more lesson in creative work-arounds from Friedkin just as shooting was nearing an end, when the director joined him for a walk on the beach in Malibu after the film’s producers raised concerns about the film’s planned ending – SPOILER ALERT – in which Petersen and Dafoe’s characters simultaneously kill each other, prompting dark twists of fate for the remaining players.

“He said, ‘Listen, the money guys are concerned about this ending because of you getting shot and all that. And they want me to shoot another ending,’” Petersen says. “And I’m like, ‘Billy, this is why we did this. This is why I did the movie. Because the script lets me play the guy the way I want to play him, and he gets what’s coming to him. So does the bad guy. The bad guy, and the good guy are the same guys. And if that’s the point we’re making, then you can’t have a guy get rewarded and another guy not.’ ”

While the director “agreed completely,” he had “promised these guys that he would shoot an alternate ending.”

“So we actually shot an alternate ending several months later,” Petersen says. “We were in a little studio and they built a little, like a room, [where] we were in some sort of distant North Pole satellite place, recovering from our wounds, having screwed it up for the Secret Service. So they hadn’t fired us. They just put us in a remote place.”

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

While they knew they were never going to use the alternate ending, they still “shot it.”

“There’s footage of it, he’s got it. I mean, it was around; we’ve seen it. It’s laughable,” Petersen says.

“And so at the end of the day, they let Billy make the decisions, and so we got to have that movie the way we wanted it,” Petersen adds, noting that he would remain close with Friedkin until the filmmaker’s death in 2023.

“Learning from him was just an amazing experience,” he says. “Actually, my whole life till he died, I learned from him. He was a great friend, and a genius, and funny as hell.”

Along with an unexpected Hollywood career and a lifetime friendship, Petersen received one other vital takeaway from To Live and Die in L.A.: a thorough knowledge of how to navigate the sprawling city of Los Angeles and its various neighborhoods. Offered his own driver to deliver him to the film’s many locations, the Illinois native instead insisted on finding his own way around.

“I’d be like, ‘No, I want to drive. I want to learn the city. If I ride with you guys, I’ll never know where I’m going,’” he says. “Same thing with CSI. We shot all over L.A. County on CSI, and it was great because I would drive to all those locations. And so now I know the Valley, I know the Deep Valley. I know Ventura, I know Orange County. Yeah, I got it all.”

“And now of course, I get in the car and they put the GPS on, and I’m like, ‘Turn that off! I can’t do it!’” he laughs. “My wife goes crazy. The lady [navigation voice] comes out and goes, ‘Take a left at the next—’ ‘Shut up! I’ll decide when I’m going to take a left! I know where I’m going!’ ”